Our collective bad decision making aside, the show's organizers bear just as much blame for the chaos as us last-minute, one-stop shoppers. Grand Palais has several different gallery spaces and unfortunately this show was on in the same claustrophobic caverns where I fought my way through 200 plus paintings at Picasso and the Masters earlier this year. Cramped tighter than a muscle spasm, lit with all the might of a medieval confessional and boasting an inconvenient staircase whose downward spiral halfway through the exhibition breaks up the flow of viewing with the same delicacy that a reeling hammer breaks up a cube of ice, this space is just not compatible with vast exhibitions and large crowds. Why it’s continually used for such shows is one of the greatest art wonders of the century.

I was hoping that the textual notes and the audio guide would help me better sort through all this exquisite muck and mire, but alas, no such luck. The textual notes were terribly esoteric, full of alienating polysyllabic words that confused far better than they enlightened. Trying to use the audio guide was a supreme lesson in patience. Chronology was cast to the winds as paintings corresponding to the guide’s numbers 19 and 29 sat side by side, notes on painting 31 came well before I even entered the room bearing 30 and I never did find the masterpiece that warranted note number 10. Oh well…

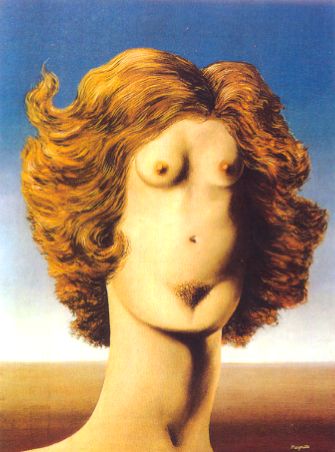

But, as they say, the show must go on and the lofty aim of this one was to examine the way in which ambiguity and hidden and double images inhabit paintings and sculpture, in particular those of Arcimboldo, Dali and Raetz.

My passion for art is steeped in the Renaissance and so it was really for Giuseppe Arcimboldo that I suffered through all this pandemonium. This past spring I taught a one week children's art course where we spent two days doing Arcimboldo style self-portraits, dismembering newspapers and magazines for images of everything from race cars to high heels, from hamburger buns to eyeballs, with the aim of re-creating the odd genius of one of the 16th century’s most unique talents. Arcimboldo is renowned for painting portraits – most notably those of the Habsburg's in Vienna where he was the much beloved court painter – made entirely of other images. The most famous examples of this technique are Arcimboldo’s Four Seasons in which he renders portraits representing not only spring, summer, autumn and winter, but also the four temperaments - sanguine, choleric, melancholic and phlegmatic – using images relevant to the season. Of these four portraits Spring, composed of colorful blooming flowers and foliage, and Autumn, with a head made of grapes, leaves, a pumpkin and a potato nose sitting atop a broken harvest barrel, were on display (I'm assuming Summer and Winter remained at their permanent home down the street, the Louvre). Arcimboldo’s Gardner was also on display, a reversible delight that, right-side-up, appears to be a bowl full of seasonal vegetables but upside-down is revealed as the head of the gardener who’s harvested them.

Next to Arcimboldo, Salvador Dali, the undisputed poster child of the Surrealist movement, was perhaps far more adept than any other artist at imbuing his work with optical illusions. In fact, Dali’s dabbles with ambiguity are philosophized in his idea of the "paranoiac critical,” in his own words the "spontaneous method of irrational knowledge based on the critical and systematic objectivity of the associations and interpretations of delirious phenomena." In non-Surrealist jargon, this means that Dali sought to link things or images that are not normally related which is often disconcerting for the viewer. On canvas these “phenomena” appear, as Dali coined them, to be “double images” (think of the pocket watch melting over the eye-lashed monster center stage in the famous Persistence of Time). Several Dali’s were on display including Portrait of Madame Isabel Styler-Tas, Endless Enigma and The Three Ages as well as some drawing studies. Unfortunately, the majority of Dalis resided in a small curved room hemmed in by crowds at the end of the exhibition and, by the time it was reached by anyone who wasn’t popping valium, was just too exhausting and overwhelming to enjoy.

I confess I don't know much about Swedish sculptor and installation artist Markus Raetz and thanks to the fact that I encountered the majority of Raetz's work after the last strains of Dali and about the same time the museum custodians began barking their “clear out, closing time” orders, I'm not much wiser than I was before. However, seeing as I'm no stranger to the vino, I found it quite a propos that the one Raetz sculpture I was able to commune with was Big and Small, a bronze working of an average-sized wine bottle dwarfed by a large wine glass full at the bottom and compressed at the top. The obvious provocation here is “how did so much wine pour forth from such a small bottle,” exemplifying how Raetz's work focuses on the visual discrepancies between illusion and reality and, as such, how his sculptures metamorphose in appearance from varying angles and vantage points. All the more fitting that I should encounter this piece at the denouement of disorder since the only thing capable of assuaging my aggravated nerves after all this ZIP-file illusion was the reality that my good friend Bacchus was eagerly awaiting me at home.

Although the overreaching line-up in a too-small and awkward space was ultimately overwhelming, One Image Hides Another was nonetheless comprised of extraordinary artists and works that shed light on larger questions of perception and duplicity. What do we perceive in a work the first time we look at it? The second time? The third? Do we see something new each time or continue to focus on the same thing? Do we see only what we want to see, what the artist, through the mystifying juxtaposition of shapes and images, instructs us to see, or is there something else to be gleaned that exceeds even the artist’s intent? How do we interpret a visual reality composed entirely of illusions, of fictions that collectively appear as facts and what, if any, comment does this visual trickery make about us and the human condition?

No comments:

Post a Comment