Before moving to Paris last July I spent two and a half years guiding tourists from all four corners of the earth up and down the seven hills of Rome. I gave homilies about the history of Western civilization under shady umbrella pines atop the Palatine Hill, spun yarns about the brutal and bloody history of the games in the magnificent shadow of Vespasian's Coliseum, marked the milestones of the Appian Way while recounting Saint Peter's fateful

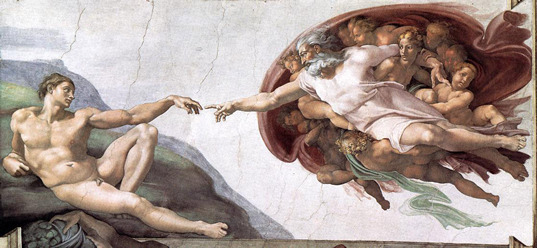

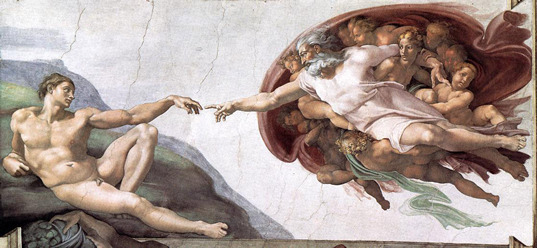

domine quo vadis encounter with Christ, pontificated at the foot of the altar where the twenty-thrice-stabbed body of the great Gauis Julius Ceasar was creamated among hordes of Romans in the ancient Forum, soliliquized the story of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel while the glory of it shone down from above, and encouraged my superstitious minions to splish splash their extra euros away in the famed Trevi Fountain for

una tornata to the Eternal City one day. And after rolling history, to paraphrase the grand old T.S. Eliot, into a ball during an onsight bird's eye view into 2,500 years of it, what do you think was the most oft question I got from my holidaying peanut gallery?

How and when did Christianity supplant Roman paganism?

Nope.

How did the Romans succeed in amassing a fifty million person empire in less than three centuries?

Nope.

Did Nero really play the fiddle while Rome burned?

Nope. (And for the record mythbusters, the fiddle didn't rear its ugly head for another 1500 years after the great fire in Rome of 64 A.D. "What is the lyre" will get you another crack at Jeopardy).

Were the Pope and Caesar friends?

Sadly I heard this innane query so regularly that I began to question the history taught by Western civilization.

Did Michelangelo paint the Sistine Chapel laying on his back?

Surely the runner up to the most oft asked question, but no cigar. (And if you're interested in dispelling this impossible myth check out the section to the right entitled "The Most Infamous and Uncreative Lie in Art History.")

So, with the blood of kings, emperors, soldiers and martyrs under their dusty, Croc'd feet, what was my clients' Sixty-Four-Thousand-Dollar question?

WHAT'S UP WITH ALL THE GRAFFITI IN ROME?

Yes ladies and gents, Rome is drenched in graffiti and one can't fault the squeaky clean graffiti-is-a-pox-on-humanity minded tourist's curiosity or shock that everything from ancient Roman edifices to the fortress-like brick walls surrounding Vatican city have been scrawled, scratched, spat and sprayed upon to such a degree that it's easy to confuse your Roman holiday with a trip back in time to the late 70's Bronx. I myself grew up on the graffiti-riddled Venice Beach Boardwalk running amok with taggers and graffiti artists at a time when the manhunt for the LAPD's most wanted tagger, Chaka, was a regular nightly news headline and even I was amazed at the profundity of motley markings when I first arrived. But with my ghettochild roots, my amazement was steeped in something quite different from that of the average bear. I was struck by the Roman grafitiosi's emulating my rough, tough and dirty American youth street culture. My disturbed clients, on the other hand, wanted to know how in the Pope's name such a thing is permissable in the showplace of Rafael and Michelangelo's Renaissance.

Imagine the dropping jaws as I retorted that these stars of the quattrocento were guilty of graffiti too. Allow me to explain.

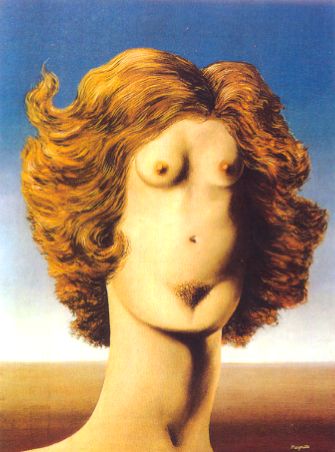

Graffiti - plural from the singular Italian graffito - is derived from the Greek word graphein, "to write," and refers to markings, drawings, scribblings, or scratchings - generally illicit or obscene ones - made onto a surface such as a wall, pavement, post, etc. Markings like this have existed since ancient times and can be found all over ancient Roman territory, my personal favorites being the instructional graffiti, shall we call it, at Pompeii's brothel and the directionally challenged penises scratched into the walls of the Coliseum that point the path to where randy game patrons could pass a slaughter-free intermission in the comforting arms of a prostitute. Since it wasn't in my best interest to share these examples on my family friendly tours I would lead clients to images of gladiators graffiti'd in marble that were displayed inside the Coliseum and explain how graffiti was the result of a number of things going on in ancient and in modern Rome alike. L'ennui was often a culprit. If you were waiting hours at the Coliseum under the miserable hot Roman sun for a new splattering batch of blood and guts you'd probably resort to a bit of doodling in the stones too (or check out those happy hookers - take your pick). Likewise, if you're spending eons on the 40 or 64 bus trying to get across town you might be given over to the same urges. Politics, maybe a disagreement over or a point of view behind them, was a notorious motivating factor behind putting your name or ideas in stone. If imprisonment, mutilation or death is the result of freeing one's voice then surely an anonymous scrawl, big or small, is the better choice - in the times of Augustus and Berlusconi alike. Another reason - and one we're all guilty of - is for the twofold sake of nostalgia and recognition. We've all carved our "I ♥ So&SO" initials on a prominent piece of bark somewhere in this world. Why? Because there's a special kind of irony in overcoming our anonymity with our anonymity. Sure, we want to remember our connection when we return but we also want others to recognize it when we're away - even if they have no clue who we are. Others see that we still exist in this place even if we're not here and they're left wondering who we are, why we came, and how we left. This is precisely why Michelangelo, Raphael and Pinturrichio hit up the walls of the emperor Nero's Domus Aurea when they visited during excavations in the 1500's.

M + R + P

Westside Renaissance Crew Wuz Here

BIATCH!

If Rome's greatest Renaissance artists recognized and appreciated the social relevance of graffiti to the point of perpetrating it on ancient stone then surely - blaspheme! - we can get on board too. From the most offensive fat black Sharpie marrings on our commuter trains to the funkadelic art pieces that infiltrate Coca Cola and IBM ad campaigns, graffiti is part of our collective human legacy and for some more than others doing it is coded in the DNA. What you can't say for fear of persecution, for lack of oratorial eloquence, for fear that spoken words vanish into thin air, for fear that no one is listening or that you lack the individual power to be heard, or simply just because you spray it better than you say it you can bomb like Hiroshima all over the goddamn walls.

And Hiroshima'd rainbowliciously all over the walls at Grand Palais is T.A.G. (Tag and Graffiti), the most courageous and comprehensive cornucopia of dropped bombs ever put on public display. Mingling Aerosol Art with the world of High Art is nothing new (take a look back at the early 80's PBS documentary Style Wars that features a few young artists bragging about how much their pieces fetch), but what sets T.A.G. apart from previous graffiti expos is the monumental number of artists involved and amount of pieces they produced. Over 150 artists of both renown and underground fame were commissioned by architect and gallery owner Alain Dominique Gallizia to drop an astounding 300 tags and graffiti pieces. Known as the Gallizia Collection, le Monsieur's vision as a down and die-hard devotee of street art was to gather a near impossible to conceive forty years worth of international bombers at his studio just outside of Paris to complete two original 180 x 60 canvasses . The first piece showcases the artist's tag, or street name, and the second is an interpretation of "Love." The result - intellectual art critics/theorist/freaks who discard street art as junk or any of my former graffiti-is-a-pox-on-humanity minded clients may take offense here - is the most exceptional room full of multiple talent I've seen since Picasso and the Masters showed at Grand Palais earlier this year.

Naysayers may dare to detract the credibility of a graffiti exhibition at this posh Parisian palace but with a show that commences with a nod to arguably the most famous east coaster to push the envelope of graffiti-as-art next to Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, such a task is more trouble than it's worth. An image of Basquiat's

Hollywood Africans and a shout out to his friends and fellow graffitiosos Toxic and Rammellzee (both of whom have pieces on display) is just the kick start such a daring show deserves (although the

original Basquiat would have been preferred). Lighting the stroll down vandalism lane next is a massive pink, gray and black lettered hanging with the infamous runny scrawl of TAKI 183, the 1970's NYC train wrecking terror who put east coast graffiti on the

national map. The full text of the 1971 New York Times article "Taki 183 Spawns Pen Pals" is blown up for all to read. The nostalgia continues with a video screen that features short interviews with the likes of Gallizia and NYC spray can pioneers Seen and Quick who discuss the formation of the collection and encourage visitors to respect the "stylistic evolution" of graffiti aesthetics. There is also compelling introductory text written by a legend in his own right, Henry Chalfont, author of

Subway Art and director of the aforementioned

Style Wars. Chalfont explains street art's NYC subway genesis and pays tribute to how these faceless "wild style" pioneers attained "Ghetto Celebrity Status" by arming themselves with little more than a can of paint and an alter-ego to war with the inner-city trains to create "a visual metaphor in which the energy of the soul finds expression in the circumstances of the given life."

And now... let the ghettofabulousness begin.

I was astounded as I entered and did my dizzy blond best to take in the prodigious spectrum of colors, bold and undulating shapes and mesmerizing wild style calligraphics of blocks, bubbles, swirls and strokes that ran along the length of the long, singular gallery's walls. I admit I was a tad hungover, but nursing one or not I don't know what could have prepared me for the stunning visual assault of colors, images and light that enveloped my senses. The collection is showing in the south gallery of the Grand Palais, a stripped down, unfinished space under construction with high ceilings, gritty exposed brick walls and endless oodles of cascading natural light that deli

ciously illuminate every last inch of the canvases. These elements along with speakers interjecting the subtle and intermittent street sounds of shaking cans and spraying paint came together for what was one of the most complimentary uses of gallery space I've encountered at a temporary exhibition. The graffiti canvases were arranged on the walls chronologically (on the left wall from 1969 - 1988 and on the right from 1989 - 2009) with each artists' two pieces placed side by side in a top-to-bottom row of four artists. A simple yet ingenious arrangement, like much of the graffiti itself.

It's impossible to give proper props to all on display but I will say this: with the exception

of a handful of pieces that were clearly struggling overall the collection was

incroyable. It was evident that some pieces were born of sheer fun, that some were exceptionally dark and that some were more masterful, captivating or creative than others (the distinction and the talent between old and new school artists was visible). But make no mistake - for as erratic and torrid as some of the pieces may appear there was an abundance of wizardry and wisdom written on the walls. For a standout many it was clear what "Love" meant - the trains, the cans and NYC. Numerous pieces by artists like Ces, Duro and Faust featured brilliant depictions of the Big Apple skyline, its trains bombed and careening off the tracks, personified spray cans and pictures or odes of love to it. My personal favorite ponderance on Love was Duster's artfully executed cautionary tale with Love as yellow brick road to the city flanked by a sign proclaiming it a "road to nowhere." For others Love was a headphoned baby in the womb, a bleeding heart, a portrait of a lover, an open eye, an abstract smattering of colors or a politic of peace like Freedom's tribute to Ghandi and MLK. Some artists like New York's Rammellzee took graffiti well beyond the can to create a metaphoric mixed media piece while others like Other (no shit, that's his name) skipped calligraphy entirely for image. The amount of international artists in the collection was also astounding. Next to the U.S., France had a prominent amount of it's artists on display as well as Germany, New Zealand, Australia, Tawaiin, Austria, Iran, Belgium, Holland and even Iceland whose Fridricks has got to be giving Bjork a run for her money as the supa dupa dopest femme fantastic our icy neighbors to the north have turned out.

For those of you who can't get to the expo before its closing date, Monsieur Gallizia has taken you into consideration. He has no intention of dividing or selling any of the pieces and instead has vowed that they will travel the globe as a permanent collection. If only our Renaissance patrons would've made the same commitment to their artists (Michelangelo's ceiling isn't property of the Pope - it was sold for an obnoxious amount of ducats to a Japanese broadcasting company called Nippon - far more of a sacreligious selling out than any graffiti I've ever seen on exhibit). So unless you haul ass to Rome you'll never have the Sistine Chapel in your backyard, but if you keep your eyes peeled T.A.G. just might come bombing on your train next.

T.A.G.

Grand Palais, Avenue Winston Churchill

South West Gallery, Door H

March 27th - April 26th

Monday thru Friday, 11 a.m. - 7 p.m., open late Wednesday and Saturday until 11 p.m.